KARNEVAL-FASTNACHT-FASCHING

Carnival is celebrated in many parts of the world. It combines a number

of old fertility rites and customs like the driving out of winter. Its

existence and origins are well documented in early mythology and

primitive drawings. In the center of primitive religious rites and

rituals stand the mask, dance and the procession. The human desire

to disguise, to assume a different role, is as old as humankind itself.

Fertility rites, often connected with orgiastic feasts, took place in

many early cultures.

Carnival is celebrated in many parts of the world. It combines a number

of old fertility rites and customs like the driving out of winter. Its

existence and origins are well documented in early mythology and

primitive drawings. In the center of primitive religious rites and

rituals stand the mask, dance and the procession. The human desire

to disguise, to assume a different role, is as old as humankind itself.

Fertility rites, often connected with orgiastic feasts, took place in

many early cultures.

"Fastnacht" = "Eve of the beginning of the fast," (Fasching is a

variation see our site) was initially named and reserved for the Tuesday Eve

before Ash Wednesday. "Fastnacht" was the last celebration before

the lean and somber time of Lent. The exact date depends on Easter,

which falls on the Sunday after the first full moon following the

vernal equinox (app. March 21). Since the 13th century it began

earlier and earlier before Ash Wednesday. The wild celebrations

of the change of the seasons at the winter solstice were eventually

relegated by the church to the time between January 6 and Ash Wednesday.

This has become known as the carnival season. Thus the climax of

"Karneval"--the last three days before Ash Wednesday, including Rose

Monday--are roughly between mid-February and mid-March. That is--with

the exception of the "Alte Fasnacht."

The "Alte Fasnacht" (old Fasnacht) begins on the Thursday after Ash

Wednesday and ends with the "Funkensonntag" (Sunday of sparks), the

ceremonial burning of the "Fasnacht." There are 40 days of Lent. But,

if one counts also the Sundays, one comes up with 46 days. The Sundays

were, at some point, excluded by the church as little "Easters." Some

of the towns and villages in the area around Lake Constance still hold

to the old tradition of counting the Sundays as part of Lent, which

brings it 6 days closer to Easter. The fires on Funkensonntag have

been documented since the 15th century. They are in response to the

Church's insisting on a visible end to Carnival celebrations and on

a public "burning of the spirit of Fasnacht."

Humans always tended to use the last days before a period of fasting

to enjoy life once more to the fullest. In the past, during the forty

days of Lent, faithful Catholics were asked to adhere to many severe

restrictions. With the enforcement of restrictions upon eating,

drinking and sexuality, "valve customs" developed, occasions "to

live it up," to satisfy bodily desires and thus restore a psychological

balance in individuals and populations. Today only Ash Wednesday and

Good Friday before Easter are regarded as fast days, but Catholics are

still expected to stay away from public amusements during Lent. In the

midst of winter doldrums Carnival serves as a "valve custom," which may

explain its widespread popularity and longevity.

Today similar celebrations take place on a grand scale on New Year's Eve in Times Square NYC and Mardi Gras in New Orleans in the US. .

Many scholars used to explain Carnival traditions as remnants of pre-Christian, Teutonic or Celtic rites. However, closer research revealed

that many features, can be traced to end-of-the-year festivals which were celebrated during the winter solstice as the birthday of the sun god, honored not only by the Germanic peoples, but also by Egyptians, Syrians,

Greek and Romans under differing names. In Rome there were two

celebrations that influenced carnival. Around December 25, there

were the Saturnalia, celebrated in honor of Saturnus, protector of

the fruit of the fields and of wealth. The first festival of the new

year was the Lupercalia, honoring the pastoral god Faunus. Many

customs made their way from the Renaissance and Baroque courts into

cities and towns and from there into villages. Other customs evolved

in the more recent past.

Saturn was the Roman God of Peace and Plenty, and for the period of

his festival everyone became equal. The festival of Saturnus was famous

for the temporary suspension of the authority of the higher classes over

the lower and of masters over slaves (Mythology, p. 164) The established

order was turned upside down: men dressed as women; masters waited on

their slaves. They elected a special regent, the forerunner of the

modern Prince Carnival. For the duration of the holiday a 'king' was

elected to act as master of ceremonies--making his own laws and

enforcing the most ridiculous whims.

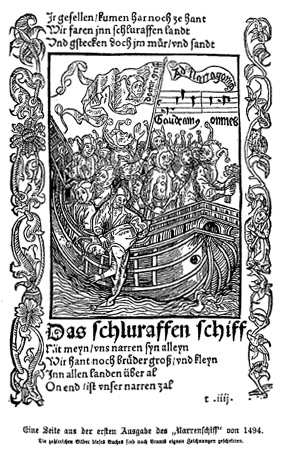

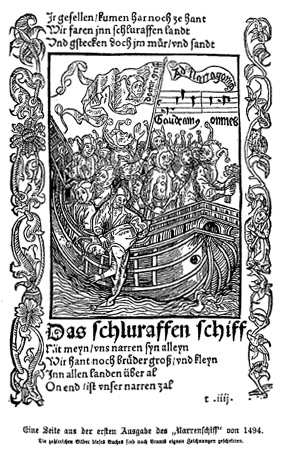

The term "Karneval" does not, as often assumed, originate from the

Italian "carne" = meat and "vale" = goodbye, but from the Latin "carrus navalis"; = the ship of fools. In the city of Babylon a

magnificently decorated ship on wheels, pulled by the faithful,

was brought to the temple of the god Marduk. Similar "ship chariots"

were part of the rites honoring the Egyptian goddess Isis. The Isis

worship, after penetrating into Greece, maintained itself in Rome

until Christian times (Lau, p. 19). The celebrations of the goddess

Isis have parallels in other cultures. The Germans honored "mother

Earth," Nerthus, a fertility goddess with similar rites.

These pagan customs maintained themselves until well into the middle

ages. The Christian church fought them valiantly, but with little

success.

In 1133, Abbot Rudolph of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Trond in

Eastern Belgium still described a spring festival, during which

a peasant, who had built a ship on wheels at Cornelimunster not

far from Aiz-la-Chapelle, drove his vehicle to Mastricht and

thence to Tongress, wildly acclaimed by the populace during his

journey (Lau, p. 21).

In 1494, in time for the "Fasnet" in Basel, Sebastian Brandt, Professor

of Law and Poetry at the University of Basel, Switzerland, published

"Das Narrenschiff" (The Ship of Fools), in which he describes all

manner of fools and their individual vices. In a woodcut of the

first edition, fools are depicted in close fitting caps with

donkey ears (Eselsohren) and little bells at the ends. A rooster's

crest is located on top of the head, directly between the ears and

descends down to the nape of the neck. The ship filled to the brim

with fools is floating without oars and rudders down the Rhine.  The "Narrenbaum" (Fools' Tree), a relative of the Maypole,

put up by some "Fools' Guilds" in Fastnacht Celebrations. i.e. in Cannstatt, is connected to the medieval iconography of the Tree of Life and the Tree of Awareness. By the 15th century it was depicted more often as a tree on

which fools grew.

The "Narrenbaum" (Fools' Tree), a relative of the Maypole,

put up by some "Fools' Guilds" in Fastnacht Celebrations. i.e. in Cannstatt, is connected to the medieval iconography of the Tree of Life and the Tree of Awareness. By the 15th century it was depicted more often as a tree on

which fools grew.

Since these "heathen excesses" could not be suppressed by the Church,

they were gradually supplied with new symbolism and adapted to the

religious calendar. The "carrus navalis" of Isis became "the ship

of fools" of Sebastian Brandt, depicting sinful man as a fool who

reaped death for his foolishness. "Carne vale!" (flesh good-bye!)

became a part of the Roman-Catholic church year. Today, the "foolish"

late winter days, dedicated to merrymaking and fun, which precede

Lent, are now known as "Carnival."

Up to the Middle Ages carnival celebrations were boisterous and fairly

simple. Beginning in the Middle Ages, the many courts in Germany, adopted

the custom and brought the ceremonies to a display of magnificent

splendor. Around A.D. 1500, under Emperor Maximilian, masked balls

following tournaments became the rage of the imperial court. They

reached their highest development during the 17th and 18th centuries,

when folkloric elements, court ceremonies and Venetian influence were

merged in splendid entertainment (Lau, p. 25).

Fastnacht or Karneval: These names indicate customs at winter's end,

which began even before Christianization. Longer days and new growth

in nature occasioned feasting and merrymaking in the central and northern

parts of Europe. In Bavaria and Austria it is called "Fasching." In

Munich the merrymaking of the fools was progressively transferred from

the streets into the ballrooms. Fasching with its dance parties, court

balls and artists' meetings became a fashion during the 19th century.

In Franconia they celebrate "Fosnat." In Buchen groups gather for the Franconian Parade of Fools In the Nü:rnberg Schembartlaufen (Schembart-run) the origins are found

in the insurrection of the local craftsmen, who in 1348 and 1349

rebelled against the powerful oligarchy running the city. In the

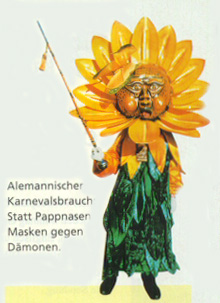

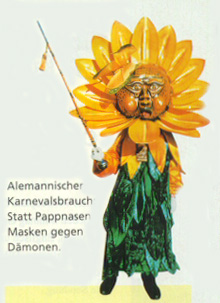

Alemannic-Swabian area Fastnacht, or "Fasnet" maintained many of its primitive features. The

Rhineland Karneval became an affair of the "burgois" who set up societies with appointed

committees. Around Mainz it's "Fassenacht," in Cologne it is

"Fasteloovend" or "Fasteleer." In the dictionary you will find

"Fastnacht" or "Karneval."

In Northern Germany, Carnival has practically disappeared. Since

Martin Luther's Reformation, Germany has been split--the North and East

are primarily Lutheran, while the South and West are primarily Roman-

Catholic. In between, however, there are many areas with mixed

denominations.

Since at least the 19th century, certain elements of the Karneval

have also emerged in largely Protestant areas. The rising middle

class in the Protestant cities began to follow the example of courts

with their staged masquerades and costume balls. Today there is hardly

a club or "Verein" in Germany that does not have its annual masquerade

or costume ball. Carnival parades are organiced even in some

predominantly Protestant cities, such as Frankfurt, on the Sunday before Ash Wednesday.

Since the 19th century, religious freedom and increased mobility of the

population (as a result of industrialization) has brought about a

further mixing of the denominations. This tendency increased

during and after World War II, especially with the displacement

and flight of more than 12 million persons from the former eastern

German territories and from what had turned into Communist East Germany.

Traditions vary, but two things are always present: Noise and masks.

The level of noise has reached new hights with the "Guggenmusik," which

has been spreading from Basel to all parts of the German-speaking Europe.

Fastnacht societies usually

prescribe costumes for the group while in areas, where Karneval and

Fasching is celebrated, especially in the large cities, the choice of

costume is up to the individual. Celebration parties, dances and balls

are accompanied by "Kappen" (caps) and masking. In many cities a Prinz

Karneval, referred to as "His Crazy Highness", is elected to head with

his princess a court of fools and lead the frolics. Especially grandiose

and intensive are celebrations along the Rhine, from the Basler Fastnacht

down to Mainz, Köln and Düsseldorf. Big pageants with costumed

marchers and masked dancers and floats are especially colorful in the

cities of Cologne and Mainz, where it is almost a civic duty to join

the fun on Shrove Tuesday. In the Rhenish celebrations on Shrove Tuesday

the crazy couple will move with their retinue into the "Rathaus" (City

Hall) to govern until midnight when the merrymaking and foolishness

comes to a sudden halt.

In the Alemannic Fastnacht/Fasnet

very old carnival traditions have remained alive. The oldest type developed

in the sheep and cattle raising cultures of the Alpine countries and its

neighboring regions. Only remnants of the customs are left. In these

celebrations, terrifying archaic masks and disguises--which may indeed

have some connection with pre-Christian fertility rites--are used. These

customs of driving out of winter and ushering in the new cycle of nature

were performed only by men. To this day certain groups, such as unmarried

young men, put on Fastnacht plays and join in the mask parades.

In towns and villages, where the Alemannic Fasnet is celebrated, there

are one or more Fools' Guilds (Narrenzünfte), and each guild has its

own history and traditions, expressed in the group's costumes and

rituals. All members wear the same costume and abide by the ritual

prescribed by the mask. Typical is the use of elaborate, beautifully

carved wooden masks. Recurring over and over are representations of

the "Wise Fool" with smooth, serene, pale faces, scary witches with

grotesque features and animal masks of all kinds--all as mythological

characters that figure in local lore and history. Children's celebrations

are usually Tuesday afternoon and evening, but they participate at

all stages of the event.

|

The Highpoints before Ash Wednesday are:

Thursday: "Weiberfastnacht," "Schmutziger Dunschtig" (fettiger

Donnerstag) - "Fasnetküchli." In some areas "Kinderfasnacht"

Saturday: "Schmalziger Samstag"

Sunday: "Pfaffen- or Herrenfastnacht"

Monday: "Rosenmontag"--has nothing to do with roses, it is derived

from "rasender Montag" (raving Monday)

Tuesday: "Fastnachtsdienstag," "Faschingsdienstag," or "Rechte

Fastnacht" (true Fastnacht); also called "Kehraus" (from "auskehren,"

to sweep out). Shrove Tuesday, because it was the day on which "shrift"

or confession was made in preparation for Lent

Wednesday: "Aschermittwoch" (Ash Wednesday)

Sunday: "Funkensonntag" - also celebrated in some areas as

"Bauern-, Allermanns-, Grosse-, Alte Fastnacht" . |

In Protestant Basel "Fastnet" begins with the "Morgenstraich" on

the Monday, following Ash Wednesday, and continues until Wednesday.

The many different festivals and customs in the various regions of

German-speaking areas, display great regional differences, but they

all refer to the "tolle Tage" (crazy days), "närrische Zeit" (the

foolish time) and the participants are Narren (fools). On the day

preceding Ash Wednesday, commonly referred to as Shrove Tuesday

(Mardi Gras), there are parades when various "Fools' Guilds" visit

each other to participate in each others parades and to share in the

fun and feasting, drinking and merrymaking.

Besides the right to celebrate Karneval in one's own fashion (often

staunchly defended) and the right to symbolically "occupy" the town

halls, the masked or disguised "fools" have traditional rights and

privileges to dispense their own justice. Common to all types of

Carnival customs, although carried out in various ways and versions,

are the "fools' trials." Community members, who have violated

unwritten norms of behavior, are reprimanded in word or deed.

Representatives of public authority may be censured in parades

and "Sitzungen" (meetings) where public events are criticized and

commented on, usually with sharp wit and irony. This feature of

Karneval has been especially cultivated in Mainz, where it has been

a tradition ever since the occupation of the city by French troops

at the beginning of the 19th century. It provided a safe outlet for

frustrations and protests.

The modern Karneval parades bring to mind religious processions, or

festive parades of Baroque courts. This kind of Karneval is easy to

participate in. A small number of people perform, making a spectacle

of themselves in the parade, while large numbers line the streets,

taking part by cheering occasionally, by buying and wearing medals

or buttons and now and then participating by singing Karneval songs.

And then there are the millions who participate by watching Karneval

on TV. Public balls and private parties, however, are also important.

--This "modern" type of Karneval is gradually supplanting the older forms.

New Karneval songs pop up every year. Karneval music has universal appeal,

sometimes even outside German borders. Composers submit compositions for

judging in hopes to have them sung by young and old during this year's

celebration. "You can't be true, dear ... " is one such song that has

traveled beyond its borders and withstood the test of time.

For those who would like to know more about Fasnacht/Fasnet,

"Treffpunkt," a German Television Series of SDR/SWF that broadcasts

half-hour programs on folklore subjects, made videos of several of

these celebrations. All videos are in color, and in German, app.

30 minutes. There are also a number of videos of Karneval celebrations.

Video One, Two, Three, Four and Five.

All of these are available from the

German Language Video Center

7625 Pendleton Pike

Indianapolis, IN 46226

317-547-1257; FAX 1+3175471263

Die Allemannisch-Schwäbische Fasnet Künzig, Johannes, Landesstelle

für Volkskunde, Freiburg im Breisgau, 1950

Carnival International, Lau, Alfred, Univers-Verlag, Bielefeld ISBN

3-920028-94-5

Narrenidee und Fastnachtsbrauch: Studien zum Fortleben des Mittelalters

in der Europäischen Festkultur. Metzger, Werner, Universitätsverlag

Konstanz, 1989

German Holidays and Folk Customs, Kramer, Dieter, An Atlantik-Brücke

Publication, Bonn: 1986, ISBN 3-925744-04-5

"Swiss Carnival Craziness," German Life, Feb./March 1999

"Cologne's Crazy Carnival," German Life, Feb./March 2000

Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Galahad Books, New York: 1975,

ISBN 0 7064 0397 5

Ruth Reichmann

Max Kade

German-American Center

reichman@indiana.edu

Further Essays by Ruth Reichmann

Fasching - a variation of Karneval

Karneval in Köln with history, events and vocabulary.

Kölner Karneval "Rote Funken" In Indy

Alemannic Fastnacht/Fasnet

Descriptions of videos of Karneval celebrations.

Video One, Two, Three, Four and Five.

Further Resources

DW's The Truth about Germany: Karneval featuring Woman's Day. And more reports from DW (Deutsch Welle)

How do you eat your Krapfen? Video One and two. Search Youtube for Krapfen

Make your own Krapfen with your students.

Berliner Pfannkuchen: Berliners or Shrove Tuesday cakes.

Reports (English) on the 2002 Karneval by the pupils of the Hansa Gymnasium, Classes 6A and 6B, in Cologne

Childhood memories / Kindheitserrinerungen from Petra's World. Side-by-side English and German

Karneval kicks off on November 11, St. Martin's Day. Woher kommt die Narrenzahl 11?

Images of Karneval in Köln - nice collection. See Carnival 1-4

Necktie on women's day?

and Der Anti-Karnevalist: Berliner zeigt 7 Rheinländerinnen an, die ihm die Krawatte

abschnitten

Exercises

Two simple Karneval quizzes for students to answer using websites.

Search the AATG database for Exercise: Comparison of American Mardi Gras and German Karneval.

Return to Customs Page.

The "Narrenbaum" (Fools' Tree), a relative of the Maypole,

put up by some "Fools' Guilds" in Fastnacht Celebrations. i.e. in Cannstatt, is connected to the medieval iconography of the Tree of Life and the Tree of Awareness. By the 15th century it was depicted more often as a tree on

which fools grew.

The "Narrenbaum" (Fools' Tree), a relative of the Maypole,

put up by some "Fools' Guilds" in Fastnacht Celebrations. i.e. in Cannstatt, is connected to the medieval iconography of the Tree of Life and the Tree of Awareness. By the 15th century it was depicted more often as a tree on

which fools grew.

Carnival is celebrated in many parts of the world. It combines a number

of old fertility rites and customs like the driving out of winter. Its

existence and origins are well documented in early mythology and

primitive drawings. In the center of primitive religious rites and

rituals stand the mask, dance and the procession. The human desire

to disguise, to assume a different role, is as old as humankind itself.

Fertility rites, often connected with orgiastic feasts, took place in

many early cultures.

Carnival is celebrated in many parts of the world. It combines a number

of old fertility rites and customs like the driving out of winter. Its

existence and origins are well documented in early mythology and

primitive drawings. In the center of primitive religious rites and

rituals stand the mask, dance and the procession. The human desire

to disguise, to assume a different role, is as old as humankind itself.

Fertility rites, often connected with orgiastic feasts, took place in

many early cultures.